Maths in code, code in music, and music in code

The other day I again encountered the statement that I must be good at maths if I’m able to read and write code. I myself remember thinking the same of others. And it was actually a contributing reason why I never considered learning programming earlier on. I just figured I wouldn’t get very far, as I don’t have the best of love stories with maths…

But as I chip away at LeetCode in preparation for the post uni job hunt, I’ve come to realise why a relatively good grasp of maths does go a long way. But it doesn’t necessarily come down to being able to calculate, more so the type of mental gymnastics that maths requires.

I would argue there are two main skills that get trained when practicing maths that help a lot with reading and writing algorithms; keeping multiple values in your head while you think, and recognising patterns. The problem is, unless you did maths throughout school (and enjoyed it enough), there aren’t really any other opportunities to practice this kind of skill.

On a High Level

I noticed this pattern the more I reviewed the LeetCode submissions that far outperform the rest. Those submissions are typically written using single letters as variables, but also achieve the correct result with pure mathematical computations and logic (instead of using data structures), which is why they’re so performant.

Through this I see the translation of mathematics into programming at the surface level. Of course, there are many levels deeper where serious skills in maths are required to solve hard problems with code (e.g, encryption).

But it was interesting to recognise the value of maths, even when not performing any mathematical calculations. The ability to keep a track of values assigned to variables is applied in other areas of life as well.

Code in Music

One of my long term goals is to understand how my previous life in music composition can integrate into my new life as a programmer on a cognitive level, rather than a creative one. It’s interesting to think how I took the ability to read music as a completely unrelated skill. And equally, how I figured I would just always hate maths.

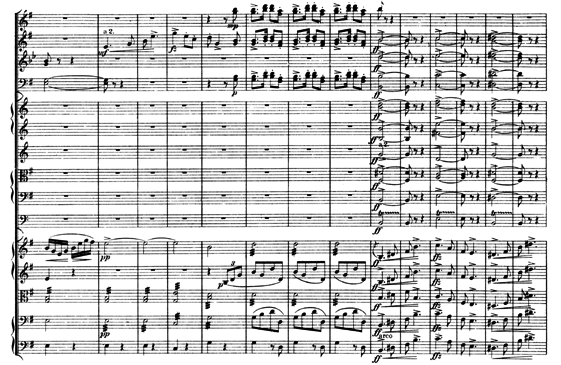

Even though it’s been a while, I can still get a general idea of what the above music sounds like just by looking at the score above. Music notation is itself code. I would say it’s easier than the code of programming languages, because to put it simply, music notation deals with constants. Every marking on that page will always communicate the same intention, time signature in 2/4, everyone plays “very loud” on bar 9 (not 0 indexed), the squiggle means to not play for one beat, etc.

The interpretation of the score is however a variable. This is what a conductor does (to some degree). Their job is to coordinate the orchestra, but they also give their own flair or interpretation to certain areas of the score. They operate within a fairly limited range of possibilities. They can’t change notes, but rather guide the energy and timing of the orchestra, which is enough to make some performances of the score stand out from others.

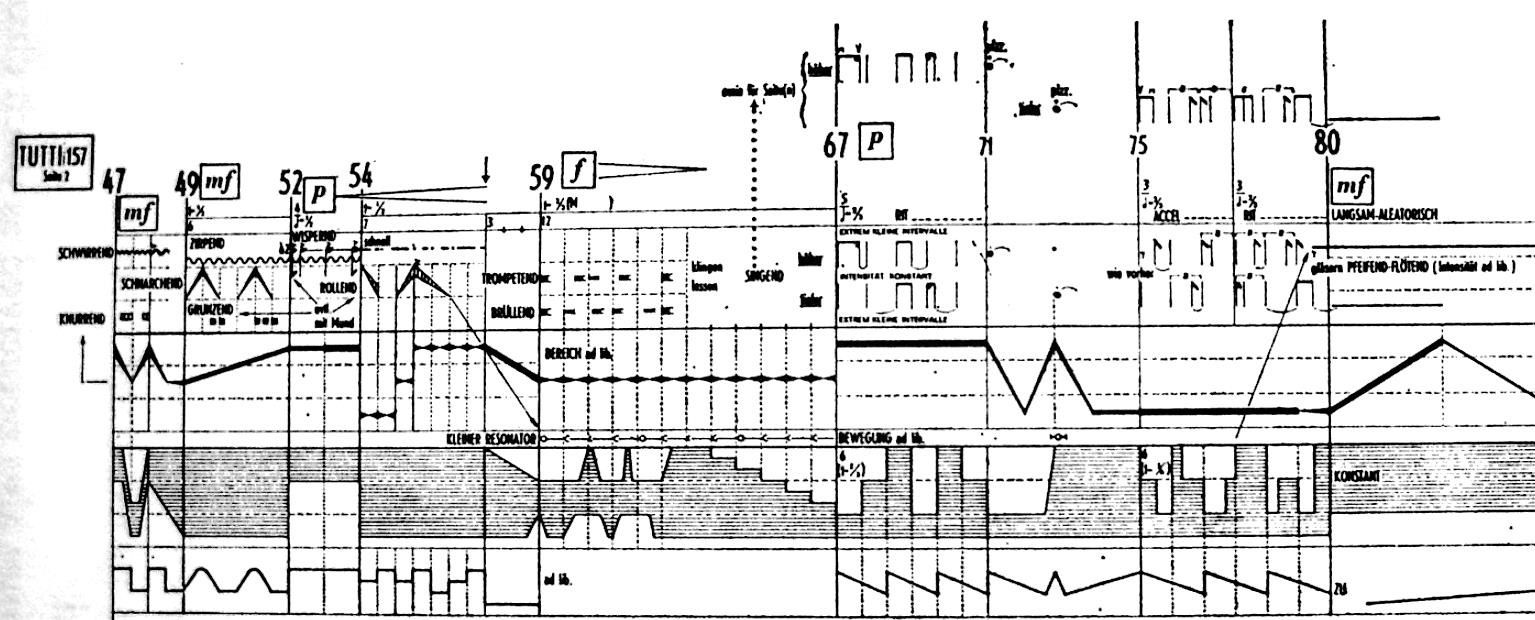

Things get a little more towards programming with the score below (Stockhausen).

This is what’s called a ‘graphical score’, and was pioneered by composers like Stockhausen. It carries over similarities from classical notation, but introduces its own syntax as well. Often, the symbology would be described in an accompanying document to the score. But other times (not necessarily in Stockhausen’s case as he was a complete control freak), it would be left very abstract and open for interpretation.

What’s interesting about graphical notation, is that you almost need less musical training to be able to interpret it. This is because when we look at a score like the one above, we can more or less pick out a narrative, as it’s laid out left to right and incorporates angles, curves, shapes and shadings that evoke at the very least a feeling of natural forces at play. Gravity, inertia, momentum, friction and fragility can all be identified in the image. And we all at some level know what heavy, rough, light, fast or hollow objects may sound like in any particular environment.

Constants, Variables, Syntax and Narrative

When I consider the above, what stands out to me is that between programming languages, maths and music, there are many shared components: constants, variables, syntax and narrative. These components simply hold different values, given different domains. Sound and movement for music, numbers for maths, and data for code.

I think if I’d been aware of this back in school, that there is much more fluidity between skill sets than is immediately apparent, I wouldn’t have convinced myself that maths and programming were two completely impossible things for me to learn.

I for one will never suggest to my children that they have a “creative” OR “analytical” mind, like I was told. It just doesn’t work like that, and creates a belief in an impressionable mind, that there are two paths, and they can only walk one of them.